Telescopes

Telescope, device used to form magnified images of distant objects. The telescope is undoubtedly the most important investigative tool in astronomy. It provides a means of collecting and analyzing radiation from celestial objects, even those in the far reaches of the universe.

Refracting telescopes

A refracting telescope is an optical instrument that uses lenses to gather and focus light, forming a magnified image of distant objects. It consists of a large convex objective lens that collects light and bends (refracts) it to a focal point, where a smaller eyepiece lens magnifies the image for viewing. First developed in the early 17th century, this type of telescope was famously used by Galileo for astronomical observations. Refracting telescopes offer sharp, high-contrast images and are relatively simple in design, with a sealed tube that protects the optics from dust and moisture. However, they also have limitations, such as chromatic aberration, where different wavelengths of light bend at slightly different angles, causing color distortion. Additionally, they tend to be heavy and expensive because large lenses are difficult to manufacture without defects. Despite these challenges, refracting telescopes are still widely used for celestial observations, terrestrial viewing, and scientific research.

Reflecting telescopes

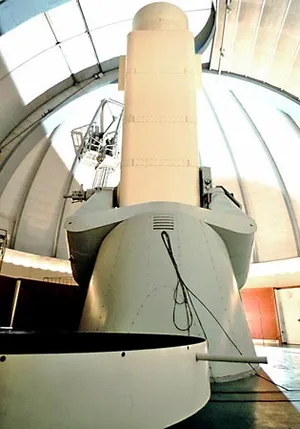

Another major type is the reflecting telescope, which uses mirrors instead of lenses to collect and focus light. Invented by Isaac Newton, this design features a concave primary mirror that gathers light and reflects it to a secondary mirror or directly to an eyepiece. Unlike refractors, reflecting telescopes do not suffer from chromatic aberration since mirrors reflect all wavelengths of light equally. They are also more cost-effective and lightweight compared to large refracting telescopes, making them ideal for modern astronomical observatories. Another advanced type is the catadioptric telescope, which combines lenses and mirrors to improve optical performance. Popular designs like the Schmidt-Cassegrain and Maksutov-Cassegrain telescopes are compact, versatile, and widely used in astrophotography. These telescopes offer the advantages of both refracting and reflecting systems, making them suitable for professional and amateur astronomers alike.

The Schmidt telescope

Multimirror telescopes